Friday, July 2, 2010

the image

Saturday, January 17, 2009

A Perfect Specimen

"Do you have any tattoos?" The technician in the neurodiagnostics lab this morning had a voice soft as my tia's chinchilla coat -- meant to soothe me into sleep as he placed electrodes onto my scalp, my chest. I laughed, "Yeah, I do." My right foot tapping nervously against the bed's rail. He moved my hair to the other side of the pillow, stuck an electrode to my neck. "What a shame." His hands were warm against my neck. "You were a perfect specimen." He was having trouble getting one of the wires to stick behind my left ear. "All this beautiful, long, unruly hair. "Perfect," he said again. "Until the tattoos." I smiled as he turned off the lights, began the process of plotting out my brain. "No. I don't think so."

I attempted to sleep, while the the Irish Catholic tech from Lake Charles, Louisiana waited to see what my unpredictable brain might do. Would it short out like the wiring in an antiquated house? Would they finally catch the ever elusive seizure? If I could just sleep. If I could just sleep because there, that's where I fall -- how could I ever explain falling and not being able to hold onto anything?

Instead, I closed my eyes, and thought of where the day would end. At St. Therese Catholic Church, at my Uncle Martin's rosary. I had no idea if my Uncle Tony or my Uncle Max would be there. No one had called to tell me yes or no. I just knew they had said I was there to represent my grandfather's family. Represent. Represent.

The last time I saw my grandfather alive, he walked up the long sidewalk to my Uncle Mario's door. He was unsteady, his walk crooked. He was thin, shrunken, but he smelled of Marlboros and his uniform never changed, crisp white shirt, ironed Wranglers and cowboy boots. He and Hector sat across from each other, recognizing each other in ways I would never understand. When my grandpa died, I held his hand. Because he had five sons, and four are left, I never thought I would be the one to represent him. And perhaps I don't. I'm just a girl.

I can no longer breathe. The room spins like a tea-cup at Disneyland. I open my eyes. "I don't feel good." I am sure the electrodes have found something. Something has spiked, but no. Everything is boring. The Irish Catholic technician tells me he can recognize the machinations of Catholic guilt. He is one of ten. He never saw his mother. She worked two jobs. His father was only around to hit them. His sisters raised him. Thoughtfully, he begins to peel off the wires. He is no longer Catholic.

After I have buttoned my coat and walked back into the lobby I am alone again. I'm lightheaded and I want nothing more than sleep, but instead I go into the new part of the hospital and have a Coke and wait until I feel safe to drive home.

A perfect specimen?

For years, I have been afraid to drive on the freeways. Will I have a seizure here? Will I have a seizure here? What would happen if I had a seizure now? Tonight I didn't care. I wasn't afraid. I merged from I-40 onto I-25 and the Sandias were glowing like altar candles in the setting winter sun. I wondered how many times my grandparents had seen these same mountains glowing the same way.

I knelt down next to my great-aunt. I took out the rosary my mom gave me during my last surgery and as my hands went over the beads, I felt my grandparents again and for the first time in a long time, I did not wonder will I have a seizure here, or here, or now? I just let myself be surrounded by family, even though this is not a family I know well. I was representing, I was alone, but I was not alone.

A perfect specimen? Not hardly, but maybe, just maybe I can get better.

Saturday, June 21, 2008

The Soundtrack of Summer

They did sing the standards. As the show was winding down, and people were packing up their chairs and ice chests they went into "Closer to Fine," "Galileo." It's funny, but I was faraway from Albuquerque in that moment. The first time I heard the Indigo Girls it was not summer. It was a bitterly cold winter day. The kind of winter day the Texas Panhandle doesn't get anymore. Perhaps it's an exaggeration to suspect global warming, but even 16 years ago I suspected global warming as the editor of my high school newspaper. I had to chip the ice off the windshield of my VW Beatle. It wouldn't start, so I called my best friend Shea for a ride to school. He pulled up in his ice blue Cutlass. The heater was on, the seats were a deeper blue and plush. When I opened the door to get in I was overwhelmed by the heat and the combined scent of Calvin Klein's Obsession and hair product. No big deal. We needed to get to school. Shea was playing a new tape -- Indigo Girls' Rites of Passage. He fixated on "Romeo and Juliet." We were both broken-hearted that morning. He was still not over his ex-girlfriend Marcy. I was still reeling over my latest break-up with Jeremiah. "Listen to this, Patti. Listen to this." We sat in the school parking lot. The car idling. Ice sliding in plates down the back window. "Listen, do you hear this line where she says. 'I keep bare, bare company. Man, I really feel that sometimes.'"

We listened to that tape the rest of that school year. It sustained us on late night drives to Denny's where we would sit across from each other and talk across chocolate milkshakes about boys, girls and loneliness. Summer began and we still listened to "Romeo and Juliet." We infused our summer with other music, specifically Tori Amos' Little Earthquakes, but always we kept the "bare company" of each other.

I can't count the number of times I showed up at his house that summer of Little Earthquakes and Rites of Passage. He assured me Jeremiah would eventually realize he loved only me. I told him there would not only be a girl but an entire town who understood his music, his fashion sense, his love of Dungeons of Dragons. The summer began with Dungeons and Dragons. We met at his house to play this game I didn't really get, even though I loved the cartoons when I was a kid. I always wanted to be Sheila (the girl who could turn invisible). Shea and Jeremiah weren't talking anymore. Shea had broken up with another girlfriend and was in summer school. We had spent a long night together listening to music, sitting at his mom's kitchen table and I went home.

Tornadoes came the next day. I stood at the kitchen window with my little brother. He hadn't even started kindergarten yet. The air was heavy, still. It was late afternoon. Mom wasn't home from work yet. I had just cleaned the kitchen. We were listening to Another Side of Bob Dylan. Adrian was only five, but he could sing all of "It Ain't Me, Babe."

Jeremiah called before the song ended. Shea was dead. His voice broke my heart. He didn't make it home from summer school. A car wreck. I don't remember very much about that phone call or the days leading up to the funeral. I just remember it was hot and humid.

I've been to two Indigo Girls shows. I always wonder if they will play "Romeo and Juliet." They never do. I suppose it's a pretty trite song -- not a hit. Last weekend I sat under these cottonwoods, thinking about my upcoming surgery, barely listening to the music. I kept thinking about dying and then I heard "Galileo." It's definitely not my favorite song, but it is on Rites of Passage. I remembered my senior year, how we kept going out to the cemetery. We decorated the tree by Shea's grave that Christmas. I remembered dancing with Shea in sixth grade, seeing him skateboard down my street when we were twelve.

Then I looked around at Annette who didn't know any of the words to the Indigo Girls, but still jumped up to look at the peacocks walking through the branches of the bosque. Kate who got excited about the possibility that maybe they would play "Strange Fire." And everyone who was dancing -- babies and adults.

Yeah, life is good

Growing Up Blue in a Red State

Since I was a kid, my mother had idolized figures such as JFK, RFK, MLKJr. and Cesar Chavez. In high school, I had teachers who proudly told me that they had never voted for Kennedy. They had cast their votes for Nixon in the 1960 election. When they assigned presentations, they would tell me to sit down after I spoke, remarking that it was unbelievable a Mexican could do better than white students. When the 1994 gubernatorial election came, we were all introduced to George W. Bush, and he won. He had Mexican nieces and nephews his family called the little brown ones.

Years later when I got into graduate school at the University of Texas, professors at West Texas were in disbelief and one actually said it. A girl like you is going to have a hard time in grad school. You would be better-suited in a school that's not so prestigious. Maybe. Thank God, I didn't try for the Ivy League. Then after I got my MA at UT, I went back to Amarillo and taught ESL where the students were older men and women, and their children were still punished for speaking their language (Spanish, Lao, Vietnamese) in school. We even had a case where a mother was sent to court for child abuse because she spoke Spanish to her child in public.

How many times during this primary campaign did we hear all the code words for racism -- hard-working, traditional, blue-collar. At one point, David Gergen of CNN wondered aloud why Senator Hillary Clinton didn't refuse the votes of racists. At one point it was clear that some of the votes she was getting was simply based on race. She even said it herself. So why not reject those votes? Admit that the Democratic Party is changing. To me, that is what I see when it is possible that Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, and Virginia might all go Democrat for the first time in decades and not because a white southerner is running, but because a person of color is running. It means the Democratic party is no longer a party of white southerners -- it's the party it has been evolving into for decades -- a party of diversity. This is what this primary season has shown me.

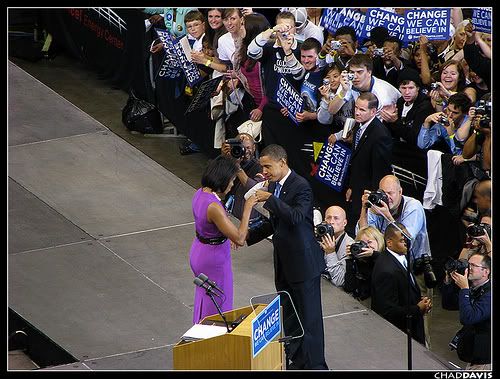

This is why I tear up almost every time I see Senator Barack Obama speak. Because for the first time I think we might have a leader who knows the experience of being a person of color in this country -- someone who knows what it means to have nothing expected of you and yet exceed everyone's highest expectations.

Monday, June 2, 2008

Going Back to Tejas

When I did go back, Austin had a fancy, huge new airport. The Paredes symposium went brilliantly. My paper was received well. I got to sit on a panel with some of the best anthropologists in the field. Was I on top of my academic game? Absolutely. We ate at an amazing Mexican restaurant. I had been craving real Tejano fajitas since I had left Texas. We drank a lot of margaritas, but the entire 3 days I was in Austin, there was a specter with me. An invisible presence that would whisper into my ear as I fell into a deep sleep, Call them. Tap me on the shoulder when I went down to the hotel lobby for my breakfast bagel. They are only 30 minutes away. You don't know when you will be here again. But 3 days is not a lot of time. The conference organizers had packed it full of events. There were all my friends. I didn't know when I would see them again either. I would always see my Uncle James, Aunt Rosie, Christopher and Christy again. I called them every Christmas, and then every January 3 for my uncle's birthday. I would get to Austin sometime soon for them, and if not there would always be the next family reunion in Santa Fe. Uncle James always went to those. I didn't call. Trying to meet up would be way too complicated. It would stress me out.

A month later my relatively new boyfriend Hector was making me breakfast and coffee. I didn't drink coffee, but he did. So he always made me a cup. It was a Saturday. The cat Mia lounged on the corner of the bed. Hector watched cartoons. It surprised me that a 46-year-old man loved Bugs Bunny, but Hector did. He said it reminded him of growing up in El Paso. I could sort of understand it, I mean I still loved Schoolhouse Rock. I knew I had to call my apartment to check my machine. I hadn't been home since Thursday. Hector turned on the TV and I picked up the phone. I knew there would be some messages from my mom, there always were, but I wasn't expecting anything from my Uncle Max. This meant bad news. My dad's brothers never called me unless something bad had happened. Probably it was my grandpa. Maybe it was my dad. My heart fluttered around like birds in my chest, in my neck, in my mouth. I watched Hector laugh at the TV. Mia licked her front paws. I called Max. In just one sentence he told me. James died last night. I wanted to scream. I was just there. I wanted to run a knife across my arm, my leg, any part of my body until it hurt as badly as I did. Hector still laughed. I didn't know what Bugs was doing. The funeral is Monday. I nodded. Yeah, yeah I'll be there. And then I was off the phone, stunned into silence. Hector couldn't go to Texas with me. Work. Always work.

My dad, Uncle Tony and Grandpa picked me up at the airport. Their cowboy hats, Wranglers and muddy boots stuck out amidst all the glass, shiny tile and burnt orange. We were West Texans in Longhorn country. The truck was stifling. No air conditioning. Dad drank a beer. My uncle stopped for some whiskey. I had no paper to present this time. The watchtower loomed in the distance. The first time I came to Austin, uncle James took me to a restaurant on La Vaca Street. There was a long wait. He couldn't sit still. He paced back and forth for 15 minutes. All my dad's brother do that. My dad, too. None of us has any patience. Why didn't I call? I could still hear his laugh over the phone. Hey Patti! Que paso? My dad had never been to a single one of my graduations -- not high school, not college. I'm sure he had and has his reasons. But James and his family were always there. Why didn't I bother to drive half an hour four weeks ago?

Tony's tapping on the steering wheel. My dad and grandpa are crying. I want to be anywhere but stuck in traffic on 183. You know, Patti, she's right. I had gone with James, Aunt Rosie and my cousins on a summer road trip to El Paso. We were listening to Janis Joplin. Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose. I laughed. I was only eighteen and I loved the talks long road trips inspired. Plus I appreciated James for still treating me like I was part of his family even if my parents were divorced. It made me feel like maybe I hadn't done anything so wrong. And after I moved to Austin, it was great to have family there. Whenever I had a flat tire, he was there to fix it. Or whenever I was lonely I could just drive up to Cedar Park and there they were, all of them. How could I not have called?

Way before James and his family moved to Austin, before I ever went to college, I used to spend every summer with my grandparents and we would drive to Lubbock to visit all of my uncles while they were in college at Texas Tech. They were all so young then, in their twenties -- newlyweds, some dating.

I would get so excited to climb into my grandparents' Cadillac and make the two-hour drive from Friona to Lubbock. All these years later one of the things I remember most about driving into Lubbock is getting to James and Rosie's house. And always the same laugh. Hey Patti! Que paso?

Friday, May 30, 2008

Living in Tornado Alley

No one in my family has ever had a basement or a cellar, but one of my earliest memories is sitting on my mom's lap in the cellar of my grandma's neighbors -- the Rileys. My knees shaking, listening to the sirens wail through the heavy, humid air. I wasn't scared. Curious is a better word. Sitting in the unfinished cellar, I wondered when we came out what we would find. Would things be upside down? Would the stereo my grandma just bought still be in the same place. Would it be in the street? What about the plants? What would happen to the dishes? When the sirens finally stopped and we emerged from the cellar, nothing had happened. Some trees had lost their branches, hail the size of baseballs had ruined some windshields, but that was all.

Fear came a few years later . . . this time we were at home -- no TV, no phone, only the radio. This is an emergency. Horses in the corral running circles and neighing to be let loose. Dogs barking. They knew something was wrong. Low, pink clouds hanging like cotton balls. My mother stands in front of the couch, talks to my dad. We have to go. It's going to hit. It doesn't matter if I'm six. I know exactly what she means. And my dad laughs. There's nothing to worry about. We're fine. She didn't listen. She had been caught in a tornado before. Once when she was a teenager, she had been working in the fields outside of Lubbock when a tornado hit. They had all lain flat amidst onions? cotton? while the tornado moved around them. She could never forget that. Of course she didn't listen to my dad. So she pulled me outside and we got in the truck, drove two miles to the neighbor's house. No one was home, but they had a cellar. It was locked. My heart nearly jumped out of my mouth. I can never forget the way the clouds started to churn. No tornado came that time either. It doesn't matter. I never felt safe in that house again.

Many years later standing in my mom's driveway my brother and I watched a tornado, thin and twisty as spaghetti spiral from the sky, drop onto the ground. It was miles away, far on the western edge of town. A rainbow formed to the east.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

The Trouble With Finishing My Dissertation

When my dad used to pick me up on the weekends, this hard rock of anxiety would crystallize deep inside my belly. I wanted to see him. I did. I wanted to see him. I wanted to see my grandpa. I wanted to see my Uncle Max, my Uncle James, my Uncle Mario, my cousins Christopher and Christy. What I did not want to see was how he lived. I didn't want to see the bare mattress where he slept on the floor of a house where my mother and I no longer lived. I didn't want to see mismatched plates and cups, or an empty refrigerator, or beer bottles. And I definitely didn't want to help him feed the horses that I suspected he had always loved more than me. All I wanted was maybe a simple lunch or dinner at Pizza Hut and that was it. That never happened. Instead I would spend all week waiting for his truck to pull into the driveway. Studying. Memorizing every capital in the United States. Reading about Presidents, American Indian chiefs, important battles in Texas history. By the time his weathered truck pulled into the driveway I was ready. I was ready for the hour and a half drive to Lubbock. We drove past windmills, through towns so tiny they didn't even merit stop lights. Towns with names like Happy and Shallowater. Marty Robbins and Johnny Cash came through the static of AM radio. But not 15 minutes out of Canyon, the quiz started. Tell me about the Alamo? What really happened at Goliad? What's the capital of Vermont? Who was the 6th President? Who was Quanah Parker? And on and on. Maybe if that had been all that would have been great. Maybe if these little 90 minute history lessons had been it, that would have been just fine. But the visits stopped. I won't say I'm sorry. I didn't look forward to seeing the way he lived. I felt guilty as hell for the way he lived and because I had not been able to stop my mom from leaving in the first place. Then the phone calls started.

I have been sitting in front of my computer for four years. I struggle to write a single chapter, sometimes paragraph by paragraph, or word by word, and so many times I hear his voice. I told your mother I wouldn't pay her one red cent in child support. I know you're angry, Dad. I know we hurt you. I know I hurt you. I'm so sorry. You know I was really smart in school, too but your grandpa always pulled me out to go work. I never got to finish a single year. I know, I know. I'm so sorry, Dad. I'm so sorry. Working in the fields is so hard. It wasn't anyplace for a little kid. I don't even know how you survived.

We had these conversations. Twenty years later I know I don't deserve a life where I write, teach and never have to work really hard. My parents, my grandparents worked in fields. What have I done? I try to incorporate my father, my family into everything I write but really I know that nothing I do will ever be enough. All I want is to deserve to be his daughter, to deserve to be their granddaughter -- to write the thing that finally really says I'm so sorry.